Story highlights

- President Obama is planning withdrawal of all U.S. troops from Afghanistan by end of 2016

- Peter Bergen: The move would invite the kind of chaos we've seen in Iraq

By Peter Bergen, CNN National Security Analyst

Video reveals ISIS recruiting in Afghanistan 01:31

Story highlights

Peter Bergen is CNN's national security analyst, a vice president at New America and professor of practice at Arizona State University. He has made frequent reporting trips to Afghanistan for CNN since 1993. This story draws on a piece that appeared in January.

(CNN)The first state visit to the United States of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Officer Abdullah Abdullah was supposed to take place in early March. But the visit was delayed because Republican leaders had invited Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to address Congress during the same time period.

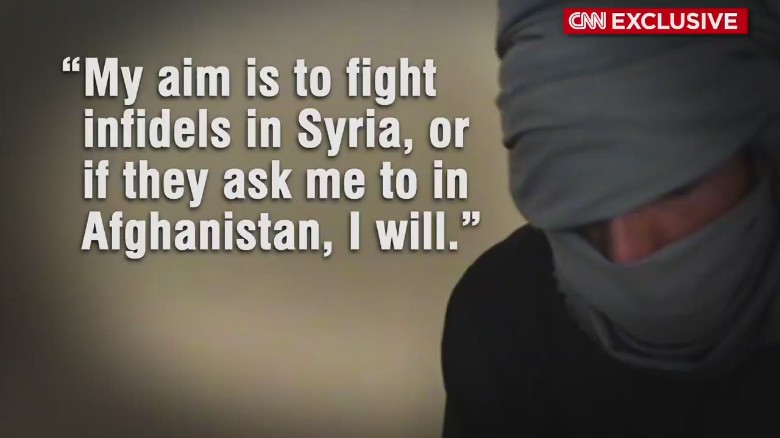

According to two Afghan government officials involved in the planning for the visit, the Afghan government believed American media attention would be largely focused on Netanyahu, so the first U.S. visit of the new Afghan president was delayed by two weeks, which is a useful reminder that there is a sound reason why congressional leaders shouldn't unilaterally extend invitations to foreign leaders. Ghani and Abdullah arrived in Washington on Sunday and have had much to discuss with the Obama administration. For the Afghan government, the timetable of President Barack Obama's proposed troop withdrawal is the key issue. Obama says that the last American troops will leave Afghanistan at the end of 2016. This happens to roughly coincide with the end of his second term in office and also fulfills his campaign promise to wind down America's post-9/11 wars. Ghani is clearly uncomfortable with the pace of this U.S. troop withdrawal, telling CBS' "60 Minutes" in January, "deadlines should not be dogmas" and that there should be a "willingness to reexamine" the withdrawal date. Is Obama's withdrawal plan a wise policy? Short answer: Of course not. One only has to look at the debacle that has unfolded in Iraq after the withdrawal of U.S. troops at the end of 2011 to have a sneak preview of what could take place in an Afghanistan without some kind of residual American presence. Without American forces in the country, there is a strong possibility Afghanistan could host a reinvigorated Taliban allied to a reinvigorated al Qaeda, not to mention ISIS, which is gaining a foothold in the region. Needless to say, this would be a disaster for Afghanistan. But it would also be quite damaging to U.S. interests to have some kind of resurgent al Qaeda in the country where the group trained the hijackers for the 9/11 attacks. It would also be disastrous for the Democratic Party, should it win the presidency in 2016, to be the party that "lost" Afghanistan. After all, the Democratic Party is viewed by some as weaker on national security than the Republicans and it is inevitable that without some kind of residual American presence in Afghanistan, al Qaeda would gain sufficient strength to launch an attack from the Afghan-Pakistan border region against American interests somewhere in the world. On Tuesday, President Obama announced that the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan would be slowed and the remaining 9,800 troops would stay there through the end of 2015. But this welcome development does not change the central issue, which is the Obama administration's withdrawal date of December 2016 for all U.S. forces. Merely because the Obama administration will be almost out the door at the end of 2016 doesn't mean that suddenly at the same time that the Taliban will lay down their arms, nor that the Afghan army will be able to fight the Taliban completely unaided. Nor does it mean that al Qaeda -- and ISIS, which is beginning to establish small cells in Afghanistan -- would cease to be a threat. An easy way for potential Democratic presidential candidates such as Hillary Clinton to distinguish their national security policies from Obama's would be to say that they are in favor of some kind of long-term U.S. military presence in Afghanistan and to argue that it would be needed to avoid an Iraq-style outcome. Similarly, as the Republican Party starts ramping up for the 2016 campaign, potential candidates such as Jeb Bush can distinguish themselves from the isolationist Rand Paul wing of the party by saying that they are committed to a long-term presence in Afghanistan. This U.S. military presence in Afghanistan doesn't have to be a large, nor does it need to play a combat role, but U.S. troops should remain in Afghanistan to advise the Afghan army and provide intelligence support. Such a long-term commitment of several thousand American troops is exactly the kind of force that the Obama administration was forced to deploy to Iraq following ISIS's lightning advances there over the past year. Selling a longer-term U.S. military presence in Afghanistan would be pushing against an open door with that nation's government. Consider that within 24 hours of being installed, the new Afghan government led by Ghani and Abdullah signed the basing agreement that allows American troops to stay in Afghanistan until December 2016. Consider also that the Afghan government has already negotiated a strategic partnership agreement with the United States lasting until 2024 that would provide the framework for a longer term U.S. military presence. Consider also that many Afghans see a relatively small, but long-term international troop presence as a guarantor of their stability. It is also not in Pakistan's interests for Afghanistan to fall to the Taliban or be thrust into another civil war. The Pakistanis have seen for themselves repeatedly the folly of allowing the Taliban to flourish on their own soil, most recently in the Taliban attack in December on the army school in Peshawar that killed 132 children. It is in Pakistan's own interest that the Afghan army is able to fight effectively against the Taliban, which is more likely if they continue to have American advisers at their side. Other regional powers such as the Chinese worry about Chinese Uighur separatists establishing themselves on Afghan soil. The Russians are similarly worried about Islamist terrorist groups located in Afghanistan and so will not stand in the way of a small long-term U.S. military presence in Afghanistan as that would dovetail with their own security concerns about the country. Keeping a relatively small, predominantly U.S. Special Forces, presence in Afghanistan to continue to train the Afghan army past December 2016 is a wise policy that would benefit both Afghans and Americans. Both the Democratic and Republican parties should adopt such a plan in their platforms as they gear up for the 2016 campaign. And Obama should do his successor a favor by leaving this important decision up to the next President.